Help Center

Online Resource Center for Information on Birth Injuries.

The term “torticollis” comes from the Latin “tortus,” for twisted, and “collus,” for neck. There are several types of torticollis, but in general, torticollis refers to abnormal positioning or movement of the neck, shoulders, and head.

Spasmodic torticollis, also known as cervical dystonia, is a neurological condition characterized by involuntary muscle contractions in the neck and shoulders. In the vast majority of cases, spasmodic torticollis affects people of middle age or older.

Acute torticollis, or wry neck, is a temporary response to a neck injury, poor posture, or exposure to cold. Painful muscles cause the neck to become stuck in an unnatural position. After a few weeks, treated with stretching and common medications, acute torticollis typically resolves itself.

Acquired torticollis, torticollis that is developed at some point in a person’s life, has a variety of possible triggers. Reaction to certain drugs, infections, tumors, and nerve damage can all cause acquired torticollis. Treatment depends on the underlying issue.

Infant torticollis, also called congenital muscular torticollis or simply congenital torticollis, is the only type of torticollis that by definition affects children and babies. Infant torticollis is completely curable, and sometimes you can treat your child at home without the need for medical procedures.

Infant torticollis is somewhat common. If not already present when a baby is born, symptoms will develop within three months of birth. Contact your pediatrician if you notice the following symptoms:

Luckily, infant torticollis is curable. However, if left untreated, torticollis can cause more serious problems. The baby won’t have a normal range of motion due to permanently tightened muscles. And since their head is held in awkward positions, asymmetry in the face and skull and even scoliosis are possible complications.

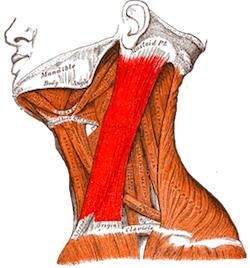

Infant torticollis is caused by an injury to the sternocleidomastoid muscle, a neck muscle which runs from the ear to the sternum. There are two sternocleidomastoid muscles in the human body, one on each side of the neck. If you turn your head from side to side, you can see the sternocleidomastoid muscles flexing.

The nature of the injury, in medical jargon, is “endomysial fibrosis with deposition of collagen and migration of fibroblasts around individual muscle fibers” which results in “unilateral shortening and thickening or excessive contraction of the sternocleidomastoid muscle.”1 In layman’s terms, scar tissue forms on the muscle, causing it to tighten.

Researchers remain unclear about exactly what causes this injury. However, it is hypothesized that this sort of injury occurs when there is some form of pressure on the fetus. For example, babies can assume cramped, abnormal positions inside the womb. First time mothers, whose uteruses are smaller than women who have been pregnant before, are more likely to have babies with torticollis.

Doctors also suspect that breech position, when the baby’s buttocks face down instead of the head, could be a culprit. Injuries to the neck can also happen during difficult deliveries, such as when forceps or a vacuum are used to pull a baby through the birth canal.

Rarely, infant torticollis is caused by something else. To give just a few examples, the sternocleidomastoid muscle could have developed abnormally, or the baby could have been born with a vision problem and is turning their head in order to see better.

In other instances, torticollis in infants is not congenital (originating before or during birth) but is acquired at some later point. It can develop due to an injury or straining of the neck, which can happen if a caretaker leaves the baby in one position for long periods of time. Infections, inflammation, and tumors are examples of the possible reasons that an infant could acquire torticollis.

In older babies and children, torticollis can be acquired for a variety of reasons, some benign and some serious. Usually, torticollis in children is the result of strain, such as falling asleep in a bad position, but it’s important to determine the cause of the torticollis if it lasts for longer than a week.

Another source of acquired torticollis is Sandifer syndrome.

Preventing congenital torticollis, which happens as a result of injuries acquired in the womb or during birth, is tricky. A doctor can try to turn a baby once it is in breech position, for example, but can’t stop the baby from becoming breeched in the first place. During delivery, your healthcare providers should avoid straining the fetus’ neck and use safe techniques to complete the birth.

Once your baby is at home, following healthy practices can prevent them from straining their neck and acquiring torticollis. Namely, you should never leave them in one position for a long period of time. You can change the position of their head while they’re playing, breastfeeding, and sleeping to promote even musculoskeletal development. However, for safety reasons, a baby should still always sleep on their back.

Time on their stomach, while they’re awake and under supervision, strengthens a baby’s neck muscles. They’ll get practice supporting their head and moving around. As much as possible, reduce time in car seats, carriers, and highchairs which support the back of the head and limit range of motion.

Your pediatrician will examine your baby in order to determine if they have torticollis, and if so, what is causing the torticollis. They will assess how far your baby can turn their head and how they respond to being placed in different positions.

It may be necessary to check your baby’s bones and muscles for anything out of the ordinary with an x-ray and ultrasound. The ultrasound will be able to see the shortened sternocleidomastoid muscle.

The pediatrician will also look for signs of asymmetry or flattening of the head, face, or neck and for hip dysplasia, a joint condition associated with torticollis. The hip joint is sometimes pushed out of place when a fetus is cramped inside the womb, a scenario which can also put strain on the neck.

Other conditions that may be causing the torticollis will also be considered by your pediatrician, like an infection, fracture, reaction to a medication, vision problem, tumor, spine defect, neurological disease, or movement disorder.

Infant torticollis is completely curable. The faster your baby gets treatment, the better. Treatment typically involves physical therapy to even out the muscles in the baby’s neck. Your doctor will teach you stretches and strategies you can use at home as well as refer you to a physical therapist.

The stretches you and your physical therapist will do with your baby loosen the constricted sternocleidomastoid muscle and strengthen the weak sternocleidomastoid muscle on the opposite side.

You can also strategically put toys and other things that the baby wants to look at in a place where they will have to turn in order to see them. Similarly, you can hold your baby so that their neck turns to the non-preferred side. Placing rolled or folded towels around your baby can help hold them in a neutral, normal position while they’re playing or in a carrier.

It’s important that your baby has supervised “tummy time.” Lying on their belly forces infants to hold up the weight of their own head, which strengthens their neck.

Rarely, if a child does not respond to physical therapy, surgery may be required to fix torticollis. The surgery, which about 10% of children with congenital torticollis need, lengthens the sternocleidomastoid muscle. A recent study found that the use of a medication called botulinum toxin could be used in place of surgery to treat torticollis.

Your baby may also need to be treated for secondary symptoms or related conditions. A flat or misshapen head is easily corrected when a baby is still young because their bones have not yet fully hardened. Special pillows and helmets allow the head to fill out to normal roundness. Mild scoliosis does not normally need to be treated, but moderate to severe cases can be improved by wearing a brace or undergoing surgery. Hip dysplasia is treated in the same way.

Seeing your baby’s head tilt in what looks like an uncomfortable position is upsetting. Luckily, there are effective treatment options, and your baby should be as good as new within a few months.

Bashir, A., et al. (2022). Effect of physical therapy treatment in infants treated for congenital muscular torticollis-a narrative review. Journal of the Pakistan Medical Association.

This study found that conservative physical therapy yielded positive outcomes. It also found that earlier physical therapy referrals significantly reduced treatment durations.

Gou, P., et al. (2022). Clinical features and management of the developmental dysplasia of the hip in congenital muscular torticollis. International Orthopaedics, 1-5.

This study found that congenital muscular torticollis was not a treatment failure risk factor in children suffering from developmental hip dysplasia. It also found that identifying CMT would allow for earlier diagnoses and treatments.

Song, S., et al. (2021). Effect of physical therapy intervention on thickness and ratio of the sternocleidomastoid muscle and head rotation angle in infants with congenital muscular torticollis: A randomized clinical trial (CONSORT). Medicine, 100(33).

This study found that passive stretching treatments significantly improved the head rotation degrees in congenital muscular torticollis infants under three months.

Chen, S.C., et al. (2020). Traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) massage for the treatment of congenital muscular torticollis (CMT) in infants and children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice, 39, 101112.

This study found that traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) massages combined with stretching significantly improved outcomes in children with congenital muscular torticollis.

Amaral, D.M., et al. (2019). Congenital muscular torticollis: where are we today? A retrospective analysis at a tertiary hospital. Porto Biomedical Journal, 4(3).

This study looked at congenital muscular torticollis. It found that early diagnoses, parental education, and conservative treatments were important to achieving positive outcomes.

Durguti, Z., et al. (2019). Management of infants with congenital muscular torticollis. Journal of Pediatric Neurology, 17(04), 138-142.

This study found that earlier physical therapy interventions achieved better results in children with congenital muscular torticollis.

Limpaphayom, N., et al. (2019). Use of combined botulinum toxin and physical therapy for treatment resistant congenital muscular torticollis. Journal of Pediatric Orthopaedics, 39(5), e343-e348.

This study found that botox injections combined with physical therapy yielded positive outcomes in congenital muscular torticollis patients.

Poole, B., & Kale, S. (2019). The effectiveness of stretching for infants with congenital muscular torticollis. Physical Therapy Reviews, 24(1-2), 2-11.

This study that stretching was an effective treatment intervention for congenital muscular torticollis. The researchers also found that earlier physical therapy referrals decreased treatment durations.