Help Center

Online Resource Center for Information on Birth Injuries.

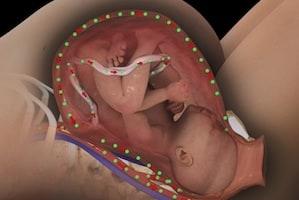

Shortly after a new baby is born the umbilical cord is clamped and then cut. Delayed cord clamping refers to the process of waiting several minutes before clamping the umbilical cord after birth. A number of recent studies have found that waiting a little longer to clamp the umbilical cord may actually have some health benefits for the baby. The results of this research recently prompted the World Health Organization (WHO) to recommend delayed cord clamping in all births. Specifically WHO advises that cord clamping should not be done until at least 1-3 minutes after delivery or longer. However, delayed cord clamping does come with some risks and there continues to be significant debate about the risks and benefits of waiting to clamp the umbilical cord.

Delayed cord clamping refers to a deliberate choice to wait or prolong the amount of time between the birth of the baby and the eventual clamping and cutting of the umbilical cord. Instead of immediately clamping the umbilical cord as soon as the baby comes out, the cord is intentionally left uninhibited for a prolonged time period. The exact length of the delay can vary, but typically delayed cord clamping usually occurs around 5 minutes after birth.

The idea behind DCC is that waiting a little longer before clamping the umbilical cord allows for continuation of blood flow from the placenta to the newborn baby. This short delay in clamping of the umbilical cord can actually increase the baby’s blood volume by 33%. More blood volume means the baby’s body has more iron which can help fuel healthy brain development.

Delayed cord clamping is not standard medical practice in full-term births. The standard of care in obstetrics right now only calls for delayed cord clamping with premature babies who are more in need of the increase in blood volume compared to full-term babies. This continues to be the accepted practice endorsed by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG). ACOG guidelines only recommend delaying umbilical cord clamping for preterm deliveries, citing a lack of evidence to support the benefits of DCC in full-term infants.

The accepted practice in full-term babies is immediate clamping of the umbilical cord within the first 30 seconds after birth or delivery of the placenta. Immediate cord clamping is considered less risky than DCC because it allows for immediate neonatal care or intervention and reduces the risk of certain neonatal complications. However, the most recent scientific studies on cord clamping seem to indicate that delayed cord clamping may be beneficial to both premature and full-term babies.

There is no debate that delayed clamping of the umbilical cord after birth allows more blood to flow from the placenta to the newborn baby, thereby significantly increasing the baby’s blood volume at birth. The health benefits of this effect in premature babies is well-recognized. The question has always been whether this increase in blood volume offered any major health benefits for full-sized, full-term, otherwise healthy babies. However, a number of medical studies have recently been published which clearly indicate that even health, full-term newborns benefit from DCC and the resulting increase in blood volume.

A study published in the December 2018 issue of The Journal of Pediatrics concluded that full-term babies receive two very distinct health and development benefits from delayed cord clamping. Specifically, URI study found that a 5-minute delay before clamping the umbilical cord results in increased iron levels and brain myelin in full-term babies.

The 2 primary risks associated with delayed cord clamping are hyperbilirubinemia and polycythemia.

Almost all of the recent studies and research on delayed cord clamping supports the conclusion that it offers important benefits for full-term babies and that the perceived risks are minimal. Immediate cord clamping is still common practice in most hospital delivery rooms, but DCC is rapidly gaining acceptance. Expecting mothers should discuss this subject with their OB/GYN before delivery.