Help Center

Online Resource Center for Information on Birth Injuries.

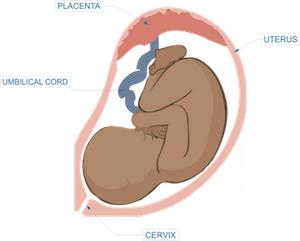

The placenta is the life-giving organ that forms in a mother’s womb when she becomes pregnant. The placenta attaches to the umbilical cord and plays a critical role in fetal growth and development.

Placental insufficiency (or “placental dysfunction,” “uteroplacental insufficiency,” or fetoplacental insufficiency) is a serious abnormality that can occur during pregnancy when the placenta does not properly form or becomes damaged. This can cause the placenta to be unable to deliver enough nutrients and oxygen to the fetus. Chronic placental insufficiency can also result in decreased delivery of calories to the fetus with intrauterine growth delay.

The placenta is a unique and complex product of human reproductive biology. The placenta forms and begins to rapidly grow inside the womb when a fertilized egg attaches to the wall of the uterus. The importance of the work the placenta does cannot be overstated.

The vital umbilical cord forms and grows out of the placenta and attaches to the fetus. The umbilical cord and placenta function together to circulate blood between a mother and baby. The placenta acts as a filtration and nutrient exchange system.

Blood from the mother flows into the placenta and deposits nutrients and oxygen. Blood from the baby circulates into the placenta and collects the oxygen and nutrients from the mother and sends them to the baby. The placenta carries out several critical functions in this process including

The placenta is also involved in the production of certain pregnancy hormones and in protecting the baby from infection. The placenta grows ahead of the fetus and continues growing throughout pregnancy. By the time the baby is born the average placenta weighs in at about 1-2 pounds. In a normal delivery, the placenta comes out shortly after the baby.

Placental insufficiency is triggered by lower than normal maternal blood flow. To carry out its functions properly, blood from the mother must circulate into the placenta at normal levels. Insufficiency results when incoming maternal blood flow levels decrease. This decrease in maternal blood flow can be caused by several medical conditions or events.

The most frequent conditions that have been known to cause placental insufficiency include:

Placental insufficiency may also be caused by mechanical complications such as if the placenta is not properly attached to the uterus or if it suddenly detaches (placental abruption).

You rarely see obvious maternal symptoms that the placenta is failing. Most mothers with placental insufficiency do not feel anything. Clues that there is something off tend to be very subtle. For instance, a mother in a second pregnancy may notice that her tummy is not getting quite a large or full as it did with her previous child. Babies suffering from placental insufficiency tend to move around in the womb a lot less also.

As a general rule, the sooner signs of a failing placenta are diagnosed the better the likelihood of a good outcome for the fetus. The key to prompt, early diagnosis of insufficient placental is high-quality prenatal care. Reaching a final diagnosis of uteroplacental insufficiency is usually the result of various prenatal diagnostic tools including:

Unfortunately, no treatment can effectively fix placental insufficiency. However, careful management can successfully minimize potential consequences and adverse effects of the condition. Appropriate management of placental insufficiency will often depend on how far along the pregnancy is and the stage of fetal development.

When placental dysfunction first presents in the latter stages of pregnancy (after week 35) a scheduled C-section will often be the best course of action. Most cases of placental insufficiency develop much earlier on in the pregnancy. Successful management of these early-onset cases is largely dependent on early diagnosis. Once placental insufficiency is diagnosed management plans will usually include the following measures:

There are many placental insufficiency success stories from women getting bed rest, often in a hospital setting with frequent monitoring.

In addition to these management measures, doctors will usually prescribe a course of steroids. Steroids help to accelerate the final development of the baby’s lungs, one of the last things to develop before birth. This is mainly a precautionary measure designed to make sure that the baby will be able to function if early delivery becomes necessary.